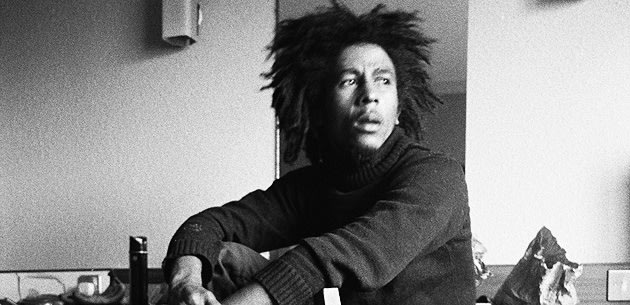

Photo by Magnolia

Pictures

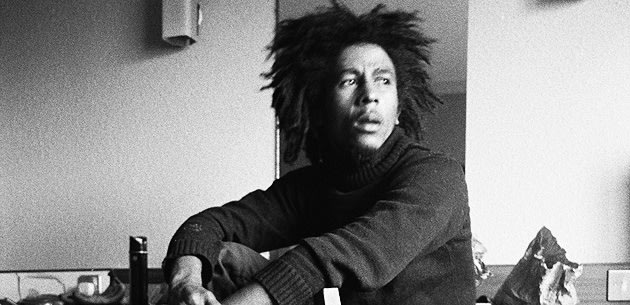

Photo by Magnolia

Pictures

If you like Bob Marley, Oscar-winning director Kevin MacDonald's latest

documentary, "

Marley,"

will bring you intimately closer to the man, his music, and his message. If you

don't like Bob Marley, go take a look in the mirror and ask yourself why you're

such a hater.

Since his untimely death in 1981, Marley's spirit has risen high above the

stature of rock star and ventured into the rarefied air of deity. His music is

sung and played the world over, particularly in developing countries, where it

gives a common voice to common struggles and touches the hearts of the

downhearted.

Such an important figure as Bob Marley deserves a master director to tell his

story. And the academy doesn't just hand out Oscars to hacks. MacDonald won his

statue for directing "

One Day in

September" (1999), the groundbreaking documentary about the Israeli

hostage crisis at the 1972 Munich Olympics. But while he won his Oscar for

directing a documentary, MacDonald is perhaps best known for his work in

features like "

The Last King of

Scotland" (2006) and "

State of Play"

(2009).

I had the opportunity to meet with MacDonald to discuss his new documentary,

"Marley." On my way to the interview, Marley's song "

One

Love" randomly played on my radio. It was that kind of

conversation, where karma was our guide. Or perhaps it was Jah? Either way, it

was an enlightening conversation with an incredible director about a remarkable

man.

*Please note: this conversation is best read with the accompaniment of any

song off of Bob Marley's "Legend."

Adam Pockross: So, "Marley." Full disclosure: I loved

it.

Kevin

MacDonald: It's hard to go wrong when you're making a film about

such an extraordinary guy. And with such fantastic music! We've got "Get Up

Stand Up," "

One Love," and then

"Three Little Birds," all on the end roller, and I'm thinking those have got to

be probably the best three playout songs of all time, for practically any movie,

and we've got all three of them. So it's hard to mess this movie up. You've got

such great raw material.

AP: You worked very closely with Bob Marley's family on

this. Did they learn anything new about him?

KM: They learned loads new. We all learned something. I

think part of the reason they wanted to make the film -- and they gave me

complete and utter freedom, and didn't interfere, and were totally honest in

their interviews, and were frank -- but I think it's because they decided, "We

want to really know our dad." They were all little kids. They were tiny. The

eldest was 14, and the rest down to zero didn't really know their dad at all.

This is a human portrait of him for them. Ziggy [Marley] said to me, "This is

the film I'm going to show my kids when they ask me, 'Who's my grandfather?'" So

that's pretty nice.

The family said, "This is your film. We'll back you up. You do what you want

to do. There's nothing you're not allowed to talk about." So then I just started

making it. Going off with no real preconceptions. I thought, "I'm just going to

go interview everybody and see what comes up." So it grew in an organic way from

interviewing just loads and loads and loads of people. And then it started to

build a picture of Bob. And every now and again, I'd phone Ziggy or his sister

Cedella [Marley], another older sibling, and say, "Can you help me with this?"

or "Do you know this person?" or whatever ... And then I showed them the

finished film, and they were thrilled.

AP: How much time did you spend in Jamaica?

KM: A couple of months, overall. About a month the first

time. You know, trying to meet as many people as I could. Then I went back and

forth two or three more times, particularly trying to get Bunny Wailer to do an

interview. A lot of people were hard to get to interview.

AP: Yeah, but you got Bunny Wailer to do a

really good interview.

KM: He's great ... he is a great value, and he's so

entertaining. Like a lot of Jamaicans, he's got great turns of phrase. They've

got a very good way with language. All these wonderful neologisms and making up

words the whole time and living language. I feel like Jamaica is a bit like

Elizabethan England, when Shakespeare and Johnson were writing. It's kind of

like language is so fluid, and they just make up words all the time, and they're

playing. Which we've sort of lost, but Jamaica's still like that. It's kind of

creative in the way they speak, and that's what Bunny's like. He's just so

creative and fun. And he's got this very ambivalent relationship with Bob and

Bob's legacy. There's a sort of jealousy and bitterness. There's also huge love

and huge respect. And he's like a guardian of Bob's memory. It's very

complicated.

AP: It's a very interesting part of the film. I keep singing

"Small Axe" [referring to a scene in which Bunny explains the genesis of the

song].

KM: Yes! I know. I love that bit. There's a few other bits;

on the DVD extras, I've got a whole "Bunny Talks" part, 20 minutes of just him

singing bits of songs and talking about how they recorded stuff in the days of

Studio One, and he goes into some detail of that. Literally just him for, like,

20 minutes, just chatting about stuff. It's really entertaining.

AP: I can imagine the DVD extras are going to be

power-packed!

KM: There's a lot of good stuff! We're all used to such

[bad] DVD extras, but this has really good ones because there's so much great

stuff. I also did another little documentary for the DVD extras; I went around

the world to all these different places in the end credits. You know, you see

Brazil, and you see Tunisia, and Tibet, and India, and wherever. We had a lot of

footage from that, so we did a 20- to 25-minute film where you go to different

parts of the globe and see how Bob is still influencing people in different

parts of the world.

AP: That was quite a takeaway from the film.

KM: Yeah, it was. That's the thing that inspired me to do

the movie in the first place: When I was in Uganda doing "

The Last

King of Scotland" (2006) and seeing how alive his presence is

there. People in the slums with huge murals of him, and quotes from him

everywhere, and his music's playing the whole time. And I'm thinking: There's no

other musical artist who has the influence and the longevity that Bob does. And

it's not just about "We love his music"; it's about "He's got a message, he's

telling us something important, spiritually." You go anywhere in the developing

world, and you find that kind of feeling about him.

AP: One of my favorite phrases that he coined is "soul

rebel."

KM: Yes! I think I cut it out of the film because the film

was even longer; I asked a couple of people, "What is a soul rebel?" I don't

think it's in the film, no, because there was a three-hour version. Bunny had a

very memorable response.

AP: What is a soul rebel to you?

KM: He's a rebel with a cause. That's from Bob Andy -- who's

a great guy, a less-known Jamaican reggae artist, some beautiful stuff he did,

still working. He's the one who said that to me. He said, "It's a rebel with a

cause, and the cause is Jah and the furtherment of Jah and Rastafari." And

that's the interesting thing, all the songs -- well, not all; there are some

that are simple love songs -- but a lot of the songs have got these hidden

meanings in them. "

One Love," for

instance, is the traditional greeting of the Rastafari; Bob just took that.

That's what Rastafari say to each other when they meet. "One love, one love." Of

course now it's taken on this whole other meaning. All his songs have this sort

of feeling of being ripped from the headlines or ripped from daily life. The

words that were around him, or the experiences that were around him.

That's why I felt an important part of the film was to take people on this

biographical journey, learn about him as a man, but for that to then inform the

way they listen to the music afterward. Because we're all so inured to the

music, and it's so ubiquitous; it's in every restaurant, every bar, and every

elevator, and you don't really hear it anymore. The idea is that you see the

movie, and then you listen to the music, and you go "Oh, OK, now I hear that in

a different way, and I'm paying attention to it again." So it takes you back to

the music.

I wish I had a share in whatever Universal music is going to make out of

selling the music! No, what I hope is that people go back. Because that's the

whole point of making any movie like this, isn't it? The point of making a movie

about an artist is to make people appreciate the art more and go back to the

art. It's all very well that you make the film, and hopefully you make a good

film, but really it's about saying, "Now go back and look at the songs." Or look

at the paintings, if it's about a painter, or look at the films, or whatever it

is.

AP: Another of my favorite phrases, not a Bob phrase, is

"Reggae is the heart of the people."

KM: I love the explanation that Bob Andy and Bunny give to

what is reggae. Talking about how you have to feel the missing beat. Reggae is

the heartbeat. [Pounds his chest.] And Lee "Scratch" Perry. [Pounds his chest

again.] I love Scratch; he's one of my favorites. He's so crazy. And so

fantastic. In fact, there's a line that he says, which to me is the key to Bob

and his success. I said to him, "Why does Bob's music live on?" And he says,

"Because of the message that he has and the way that he says it." And it's that

thing about the way that he says it: He says it in a way that you have to

believe it. It's as much to do with the way Bob sings, and the sense of honesty

and truth, so even if he's singing the simplest, almost cliched lines, there's

something about the way that he delivers it that's utterly convincing. Such

conviction. Which I think is the product of having had a tough, tough

upbringing. And seeing a lot by the time he was 20, 21. He'd experienced

poverty. He'd experienced hardship. And his voice carries all that. That's my

theory.

"Marley" opens in select theaters, On Demand and on

Facebook, Friday, April

20th.